‘No One Wants To Be’ A Bad Rider: Trainer Charlotte Wittbom Says Don’t Judge

Sweden-born horsewoman and teacher talks non-judgment, aiming high and how she fell in love with classical riding

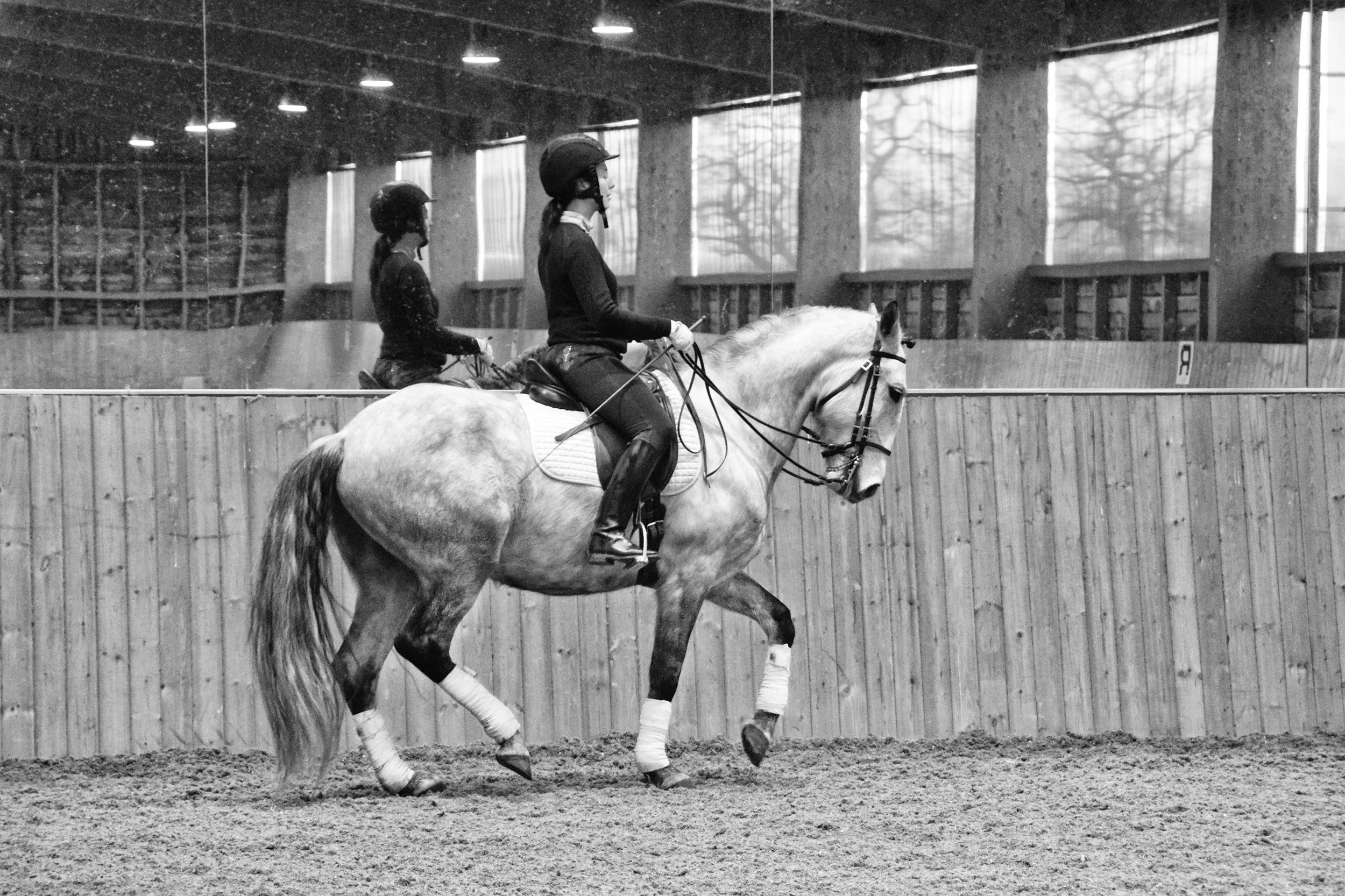

Charlotte with her ‘dancing partner’ Kalegro (sired by Negretto, who has the same father as Valegro). Photo credit: KT Equine Photography

“No one wants to be a horrendous rider,” Charlotte Wittbom tells me. I’ve asked Charlotte, a UK-based rider, trainer and teacher specialising in the classical approach, what she thinks of photos we sometimes see of horses being ridden by competent equestrians but looking a little short in the neck.

“When you see a photo of something, you never know the story behind it… it’s so complex, so I think it’s always important not to judge it by photos because it doesn’t tell you anything really, it’s just a snapshot of a split second.”

Everything from the horse’s strength, confirmation and mindset; to the rider’s knowledge, understanding of themselves and their own worries, could be affecting the horse and rider picture, she says.

In this moment I feel a little lost for words. Non-judgment is something that’s talked about a lot in yoga, and yet here I am, a yoga teacher, caught out for judging. It seems like equestrians are good at judging; not only having opinions about our peers, but judging ourselves and our horses too, sometimes without realising it.

Charlotte continues: “Nothing is perfect, everyone is on their journey, and I think what makes a good rider is that, you know, you always learn, you are humble, and you let the horse teach you.”

Charlotte fell in love with classical riding on a trip to Portugal. Photo credit: Katie Amos Photography

The journey to classical riding

I knew Charlotte before our interview: she’s taught me and I’ve watched her teach. I’ve always admired her calm and patient approach to both horse and student, and have often wondered about her background.

She describes what sounds like a charmed childhood, growing up in Sweden on a property with horses, pigs, sheep and other animals. She tells me her family always had horses and that her mum used to take her out hacking.

“I think I rode, when I could walk really.”

As a young rider she excelled in competitive eventing in Sweden, but when crunch time came, she decided not to continue.

“I just felt it was not for me really, I felt that the pressure was too much… [but] I couldn’t probably express it that way [at the time].”

The next big chapter in her career was in the UK, where she worked at the legendary Suzanne’s Riding School as an assistant instructor under Julian Marczak (who had trained in Portugal with Nuno Oliviera’s son). It was here she first learned about classical riding.

“I don’t think I knew ‘classical riding’ as such then, I didn’t label it, I just knew what Julian taught me, with my seat, and you know, starting it over from the lunge,” she says.

Following her stay in the UK, she travelled to Portugal, where – while watching a show – she “just fell into tears” and “knew immediately” that classical riding was what she wanted to do.

Far from riding to win, it “was an artform,” she explains. “Also the shows, I really enjoyed the shows, you know, you ride with classical music, you ride quadrilles, there’s a history and you feel like you’re going back in time in many ways.”

While in Portugal, Charlotte did three years as a student of Master Luis Valença and rode with Team Valença in the famous Apassionata equestrian show on three tours of Europe. She also worked as an instructor at Morgado Lusitano and was a resident at Quinta do Brejo – the former stables of Nuno Oliveira – where she hosted guests for riding holidays and taught classical approaches to horsemanship.

Riding teacher Charlotte aims to help her students have a method in their mind when they ride. Photo credit: Katie Amos Photography

Riding high

In Portugal, riding is embedded in the local culture and horses have an important role in society, she tells me. For children at the Valença’s riding school, movements such as half-pass and lead changes are part of everyday training.

Which is partly why – on the subject of non-judgment – Charlotte doesn’t conform to the idea that high school movements are only for experienced riders or certain types of horses.

To perform at Grand Prix level and achieve “that kind of quality that judges look for, is really, really difficult,” she says, but to teach a horse a bit of piaffe, leg yield, shoulder-in and half-pass, “everyone can do.”

Not only are these exercises beneficial for the horse, she says, but they can help the rider too.

At which point I ask, what is she aiming for when she’s teaching?

To help “the rider to understand, to have a method in their mind when they ride,” she explains, saying her job is to give her students exercises with the objective of creating a strong and supple horse. I wonder if one of the goals is also a relaxed horse.

“A relaxed horse, but also, as we know… [we don’t] always get relaxation first. If you’re going to be stronger, and you go to the gym, it won’t be relaxation first because it’s hard work,” she tells me, adding that it also depends on the horse you’re working with.

“Some horses are too relaxed,” she laughs, “and we need to get them a bit more, you know, up and going, and some horses have the opposite problem.”

We also want a horse to work in self-carriage. “That also takes training, not all horses can work in self-carriage immediately.”

In a nutshell, she says it’s about equipping the rider with exercises and knowledge that will allow them to rely on techniques, rather than get frustrated when things don’t quite go as planned.

“But also [to] move forward… everyone can think higher of themselves and their riding and their horses.”

“Everyone can think higher of themselves and their riding and their horses.”

Perfectionism and the UK’s ‘brave’ riders

As a teacher, Charlotte sees lots of different riders. I’m eager to know what she thinks most of us struggle with.

“There is a general thing that everyone wants to be as good a rider as they can,” she starts. “You know, everyone puts a lot of money into saddles and physiotherapy for the horse.”

But at some point, she believes it may be useful for riders to realise that they’ve done all they can for their horse, and perhaps try to understand themselves a little better – examining their own strengths and weaknesses and maybe taking up activities like yoga. She thinks it’s great that we now have things like ‘Equi-Pilates’ and mechanical horses, which can help with body awareness.

But she remains reluctant to judge, adding that in many ways, people are quite hard on themselves.

In fact, she thinks perfectionism can be an issue, with many riders not daring to try more advanced moves, and that can also stop them from moving forward.

She thinks the culture of a country can also play a part in influencing the kind of riding people do, and mentions the “very brave” riders in the UK who go hunting across open country.

Charlotte says groundwork can help a horse become stronger and more balanced in body and mind. Photo credit KT Equine Photography

Posture, core and groundwork

So what specifically can we do to improve our riding bodies and minds? Charlotte admits she’s not an expert in rider biomechanics, but believes everyone could benefit from having better posture and core strength, which will “make it easier for the horse to work under you”.

Learning about how your body might be affecting your horse and maintaining your physical fitness, is important, she thinks.

However, she says it can be difficult for riders on a horse that is unbalanced, and in these situations, working more in walk, having a method and doing groundwork can be useful.

Knowing that Charlotte is big on groundwork, I want to understand if the focus is on training the horse physically or mentally.

“Both,” she tells me. “Because… if a horse is unbalanced [physically], they are not in balance in their mind either.

“If you see the groundwork as their Pilates work, you really strengthen them, but also that communication [between horse and rider] also leads to balance in their mind,” she explains, adding that if a horse is working out of balance, quite often that can lead to him or her being reactive or spooky. “Horses don’t want to be out of balance,” she says.

And our own mindset? What could we work on?

“I think the most important thing is to be open really, and understand that things take time.”

She also highlights the importance of thinking outside the box and perhaps looking beyond the obvious – questioning whether there is an underlying problem. She suggests thinking “bigger picture” about different ways to solve an issue, and again, working with a plan or a method to avoid frustration.

“Frustration always comes when you feel like what you work with, is not working.”

“It’s like border collies”

Later, Charlotte talks about the need to understand our horses, and manage them accordingly.

For horses that are bred to work, for example, she says “it’s like border collies”: they may need a lot more exercise to be able to find relaxation, and not being worked enough could be the cause of some behavioural problems.

But she acknowledges it’s a complicated issue, and challenging behaviours could also stem from pain, the horse being misunderstood or, in some cases, him or her taking control of the rider.

“Sometimes you have horses with very nervous energy and they might need to learn to how to relax doing walk exercises. So again, it’s so complex, it depends on the mentality of your horse, what it’s bred to do, and the combination of rider and what kind of exercises.”

Consistency is also crucial, she notes (and yet another reason to have a proper method).

Rider fear is normal and can be a good thing, Charlotte believes.

Fear can be good

Before I let Charlotte get away, I need to know what she thinks of rider fear and anxiety. As a teacher, she must come across this often and have thoughts on how we can manage it.

“A certain amount of fear is good, because that means we have self-preservation,” she explains.

“It’s not negative to be scared, not at all… I will have situations where I feel fear, I will have situations where I feel like ‘ooh, you know, no, I don’t know if I want to be in this situation’. The only thing is that I acknowledge it and then find a different way… Sometimes it can be because you sit on a horse that actually is too much for you.”

If the fear feels like it hinders you, she suggests connecting with a specialist coach and finding ways to work on it, but the first step is to acknowledge fear.

“I think when you [don’t] realise that you are scared, then anger comes in instead, and when anger comes in, obviously that’s no good and the horse doesn’t understand that.”

She also recommends accepting help, saying there is nothing wrong with asking another rider to get on your horse.

“[Fear is] completely normal. We sit on absolutely huge animals and there are lots of accidents… it’s a very dangerous sport, there is no question about it.”

Forbear to judge, for we are sinners all

Hanging up the call with Charlotte, I’m armed with new ideas and tips, among them: have a method, do your groundwork, know your horse and be open-minded.

But probably the best lesson for me was the reminder to be less judgmental, and that riding a horse is far more complex than we sometimes realise.

Shakespeare was right, of course. Now when I look at photos of horses and riders, I will think twice before having an opinion.

Charlotte Wittbom - At A Glance

Charlotte Wittbom is a rider, trainer and teacher specialising in classical approaches to horsemanship. She is based in Cheshire, England, but travels internationally to deliver clinics and demonstrations and periodically welcomes guests for riding holidays and training in Portugal. Charlotte works with a diverse range of riders from around the world, spanning all equestrian specialisms, with abilities from novice to advanced. In her home of Cheshire she carries out programmes of schooling with clients’ horses and offers instruction in classical approaches to horsemanship. She holds a a teaching certificate from the Association of British Riding Schools (A.B.R.S) and a Diploma with distinction from the Centro Equestre de Lezeria Grande (C.E.L.G) in Portugal.